Mysticism: Conclusion

CONCLUSION

WE have traced, as well as our limitations allow us, the Mystic Way from its beginning to its end. We have seen the ever-changing, ever-growing human spirit emerge from the cave of illusion, enter into consciousness of the transcendental world: the "pilgrim set towards Jerusalem" pass through its gates and attain his home in the bosom of Reality. For him, as we have learned from his words and actions, this journey and this End are all: their overwhelming importance and significance swallow up, of necessity, every other aspect of life.

Now, at the end of our inquiry, we are face to face with the question—What do these things mean for us; for ordinary unmystical men? What are their links with that concrete world of appearance in which we are held fast: with that mysterious, ever-changing life which we are forced to lead? What do these great and strange adventures of the spirit tell us as to the goal of that lesser adventure of life on which we are set: as to our significance, our chances of freedom, our relation with the Absolute?

Do they merely represent the eccentric performances of a rare psychic type? Are the matchless declarations of the contemplatives only the fruits of unbridled imaginative genius, as unrelated to reality as music to the fluctuations of the Stock Exchange? Or are they the supreme manifestation of a power which is inherent in our life: reports of observations made upon an actual plane of being, which transcends and dominates our normal world of sense?

The question is vital: for unless the history of the mystics can touch and light up some part of this normal experience, take its place in the general history of man, contribute something towards our understanding of his nature and destiny, its interest for us can never be more than remote, academic, and unreal.

Far from being academic or unreal, that history, I think, is vital for the deeper understanding of the history of humanity. It shows us, upon high levels, the psychological process to which every self which desires to rise to the perception of Reality must submit: the formula under which man's spiritual consciousness, be it strong or weak, must necessarily unfold. In the great mystics we see the highest and widest development of that consciousness to which the human race has yet attained. We see its growth exhibited to us on a grand scale, perceptible of all men: the stages of its slow transcendence of the sense-world marked by episodes of splendour and of terror which are hard for common men to accept or understand as a part of the organic process of life. But the germ of that same transcendent life, the spring of the amazing energy which enables the great mystic to rise to freedom and dominate his world, is latent in all of us, an integral part of our humanity.

Where the mystic has a genius for the Absolute, we have each a little buried talent, some greater, some less; and the growth of this talent, this spark of the soul, once we permit its emergence, will conform in little, and according to its measure, to those laws of organic growth those inexorable conditions of transcendence which we found to govern the Mystic Way.

Every person, then, who awakens to consciousness of a Reality which transcends the normal world of sense—however small, weak imperfect that consciousness may be—is put upon a road which follows at low levels the path which the mystic treads at high levels. The success with which he follows this way to freedom and full life will depend on the intensity of his love and will, his capacity for self-discipline, his steadfastness and courage. It will depend on the generosity and completeness of his outgoing passion for absolute beauty, absolute goodness, or absolute truth. But if he move at all, he will move through a series of states which are, in their own small way, analogous to those experienced by the greatest contemplative on his journey towards that union with God which is the term of the spirit's ascent towards its home.

As the embryo of physical man, be he saint or savage, passes through the same stages of initial growth, so too with spiritual man. When the "new birth" takes place in him, the new life-process of his deeper self begins, the normal individual, no less than the mystic, will know that spiral ascent towards higher levels, those oscillations of consciousness between light and darkness, those odd mental disturbances, abrupt invasions from the subliminal region, and disconcerting glimpses of truth, which accompany the growth of the transcendental powers; though he may well interpret them in other than the mystic sense.

He too will be impelled to drastic self-discipline, to a deliberate purging of his eyes that he may see: and receiving a new vision of the world, will be spurred by it to a total self-dedication, an active surrender of his whole being, to that aspect of the Infinite which he has perceived. He too will endure in little the psychic upheavals of the spiritual adolescence: will be forced to those sacrifices which every form of genius demands. He will know according to his measure the dreadful moments of lucid self-knowledge, the counter-balancing ecstasy of an intuition of the Real. More and more, as we study and collate all the available evidence, this fact—this law—is borne in on us: that the general movement of human consciousness, when it obeys its innate tendency to transcendence, is always the same.

There is only one road from Appearance to Reality. "Men pass on, but the States are permanent for ever." I do not care whether the consciousness be that of artist or musician, striving to catch and fix some aspect of the heavenly light or music, and denying all other aspects of the world in order to devote themselves to this: or of the humble servant of Science, purging his intellect that he may look upon her secrets with innocence of eye: whether the higher reality be perceived in the terms of religion, beauty, suffering; of human love, of goodness, or of truth. However widely these forms of transcendence may seem to differ, the mystic experience is the key to them all. All in their different ways are exhibitions here and now of the Eternal; extensions of man's consciousness which involve calls to heroic endeavour, incentives to the remaking of character about new and higher centres of life.

Through each, man may rise to freedom and take his place in the great movement of the universe: may "understand by dancing that which is done." Each brings the self who receives its revelation in good faith, does not check it by self-regarding limitations, to a humble acceptance of the universal law of knowledge: the law that "we behold that which we are," and hence that "only the Real can know Reality." Awakening, Discipline, Enlightenment, Self-surrender, and Union, are the essential phases of life's response to this fundamental fact: the conditions of our attainment of Being, the necessary formula under which alone our consciousness of any of these fringes of Eternity—any of these aspects of the Transcendent—can unfold, develop, attain to freedom and full life.

We are, then, one and all the kindred of the mystics; and it is by dwelling upon this kinship, by interpreting—so far as we may—their great declarations in the light of our little experience, that we shall learn to understand them best. Strange and far away though they seem, they are not cut off from us by some impassable abyss. They belong to us. They are our brethren; the giants, the heroes of our race. As the achievement of genius belongs not to itself only, but also to the society that brought it forth; as theology declares that the merits of the saints avail for all; so, because of the solidarity of the human family, the supernal accomplishment of the mystics is ours also. Their attainment is the earnest-money of our eternal life.

To be a mystic is simply to participate here and now in that real and eternal life; in the fullest, deepest sense which is possible to man. It is to share, as a free and conscious agent—not a servant, but a son—in the joyous travail of the Universe: its mighty onward sweep through pain and glory towards its home in God. This gift of "sonship," this power of free co-operation in the world-process, is man's greatest honour. The ordered sequence of states, the organic development, whereby his consciousness is detached from illusion and rises to the mystic freedom which conditions instead of being conditioned by, its normal world, is the way he must tread if that sonship is to be realized.

Only by this deliberate fostering of his deeper self, this transmutation of the elements of his character, can he reach those levels of consciousness upon which he hears, and responds to, the measure "whereto the worlds keep time" on their great pilgrimage towards the Father's heart. The mystic act of union, that joyous loss of the transfigured self in God, which is the crown of man's conscious ascent towards the Absolute, is the contribution of the individual to this, the destiny of the Cosmos.

The mystic knows that destiny. It is laid bare to his lucid vision, as our puzzling world of form and colour is to normal sight. He is the "hidden child" of the eternal order, an initiate of the secret plan. Hence, whilst "all creation groaneth and travaileth," slowly moving under the spur of blind desire towards that consummation in which alone it can have rest, he runs eagerly along the pathway to reality. He is the pioneer of Life on its age-long voyage to the One: and shows us, in his attainment, the meaning and value of that life.

This meaning, this secret plan of Creation, flames out, had we eyes to see, from every department of existence. Its exultant declarations come to us in all great music; its magic is the life of all romance. Its law—the law of love—is the substance of the beautiful, the energizing cause of the heroic. It lights the altar of every creed. All man's dreams and diagrams concerning a transcendent Perfection near him yet intangible, a transcendent vitality to which he can attain—whether he call these objects of desire God, grace, being, spirit, beauty, "pure idea"—are but translations of his deeper self's intuition of its destiny; clumsy fragmentary hints at the all-inclusive, living Absolute which that deeper self knows to be real.

This supernal Thing, the adorable Substance of all that Is—the synthesis of Wisdom, Power, and Love—and man's apprehension of it, his slow remaking in its interests, his union with it at last; this is the theme of mysticism. That twofold extension of consciousness which allows him communion with its transcendent and immanent aspects is, in all its gradual processes, the Mystic Way. It is also the crown of human evolution; the fulfilment of life, the liberation of personality from the world of appearance, its entrance into the free creative life of the Real.

Further, Christians may well remark that the psychology of Christ, as presented to us in the Gospels, is of a piece with that of the mystics. In its pain and splendour, its dual character of action and fruition, it reflects their experience upon the supernal plane of more abundant life. Thanks to this fact, for them the Ladder of Contemplation—that ladder which mediaeval thought counted as an instrument of the Passion, discerning it as essential to the true salvation of man—stretches without a break from earth to the Empyrean. It leans against the Cross; it leads to the Secret Rose. By it the ministers of Goodness, Truth, and Beauty go up and down between the transcendent and the apparent world. Seen, then, from whatever standpoint we may choose to adopt—whether of psychology, philosophy, or religion—the adventure of the great mystics intimately concerns us.

It is a master-key to man's puzzle: by its help he may explain much in his mental makeup, in his religious constructions, in his experience of life. In all these departments he perceives himself to be climbing slowly and clumsily upward toward some attainment yet unseen. The mystics, expert mountaineers, go before him: and show him, if he cares to learn, the way to freedom, to reality, to peace. He cannot rise in this, his earthly existence, to the awful and solitary peak, veiled in the Cloud of Unknowing, where they meet that "death of the summit," which is declared by them to be the gate of Perfect Life: but if he choose to profit by their explorations, he may find his level, his place within the Eternal Order. He may achieve freedom, live the "independent spiritual life."

Consider once more the Mystic Way as we have traced it from its beginning. To what does it tend if not to this? It began by the awakening within the self of a new and embryonic consciousness: a consciousness of divine reality, as opposed to the illusory sense-world in which she was immersed. Humbled, awed by the august possibilities then revealed to her, that self retreated into the "cell of self-knowledge" and there laboured to adjust herself to the Eternal Order which she had perceived, stripped herself of all that opposed it, disciplined her energies, purified the organs of sense. Remade in accordance with her intuitions of reality, the "eternal hearing and seeing were revealed in her."

She opened her eyes upon a world still natural, but no longer illusory; since it was perceived to be illuminated by the Uncreated Light. She knew then the beauty, the majesty, the divinity of the living World of Becoming which holds in its meshes every living thing. She had transcended the narrow rhythm by which common men perceive but one of its many aspects, escaped the machine-made universe presented by the cinematograph of sense, and participated in the "great life of the All." Reality came forth to her, since her eyes were cleansed to see It, not from some strange far-off and spiritual country, but gently, from the very heart of things. Thus lifted to a new level, she began again her ceaseless work of growth: and because by the cleansing of the senses she had learned to see the reality which is shadowed by the sense-world, she now, by the cleansing of her will, sought to draw nearer to that Eternal Will, that Being, which life, the World of Becoming, manifests and serves. Thus, by the surrender of her selfhood in its wholeness, the perfecting of her love, she slid from Becoming to Being, and found her true life hidden in God.

Yet the course of this transcendence, this amazing inward journey, was closely linked, first and last, with the processes of human life. It sprang from that life, as man springs from the sod. We were even able to describe it under those symbolic formulae which we are accustomed to call the "laws" of the natural world. By an extension of these formulae, their logical application, we discovered a path which led us without a break from the sensible to the supra-sensible; from apparent to absolute life. There is nothing unnatural about the Absolute of the mystics: He sets the rhythm of His own universe, and conforms to the harmonies which He has made.

We, deliberately seeking for that which we suppose to be spiritual, too often overlook that which alone is Real. The true mysteries of life accomplish themselves so softly, with so easy and assured a grace, so frank an acceptance of our breeding, striving, dying, and unresting world, that the unimaginative natural man—all agog for the marvellous—is hardly startled by their daily and radiant revelation of infinite wisdom and love. Yet this revelation presses incessantly upon us. Only the hard crust of surface-consciousness conceals it from our normal sight. In some least expected moment, the common activities of life in progress, that Reality in Whom the mystics dwell slips through our closed doors, and suddenly we see It at our side.

It was said of the disciples at Emmaus, "Mensam igitur ponunt panes cibosque offerunt, et Deum, quem in Scripturae sacrae expositione non cognoverant, in panis fractione cognoscunt." So too for us the Transcendent Life for which we crave is revealed and our living within it, not on some remote and arid plane of being, in the cunning explanations of philosophy; but in the normal acts of our diurnal experience, suddenly made significant for us. Not in the backwaters of existence, not amongst subtle arguments and occult doctrines, but in all those places where the direct and simple life of earth goes on. It is found in the soul of man so long as that soul is alive and growing: it is not found in any sterile place.

This fact of experience is our link with the mystics, our guarantee of the truthfulness of their statements, the supreme importance of their adventure, their closer contact with Reality. The mystics on their part are our guarantee of the end towards which the Immanent Love, the hidden steersman which dwells in our midst, is moving: our "lovely forerunners" on the path towards the Real. They come back to us from an encounter with life's most august secret, as Mary came running from the tomb; filled with amazing tidings which they can hardly tell. We, longing for some assurance, and seeing their radiant faces, urge them to pass on their revelation if they can. It is the old demand of the dim-sighted and incredulous:—

Dic nobis Maria

Quid vidisti in via?

But they cannot say: can only report fragments of the symbolic vision:—

Angelicos testes, sudarium, et veste notthe inner content, the final divine certainty. We must ourselves follow in their footsteps if we would have that.Like the story of the Cross, so too the story of man's spirit ends in a garden: in a place of birth and fruitfulness, of beautiful and natural things. Divine Fecundity is its secret: existence, not for its own sake, but for the sake of a more abundant life. It ends with the coming forth of divine humanity, never again to leave us: living in us, and with us, a pilgrim, a worker, a guest at our table, a sharer at all hazards in life. The mystics witness to this story: waking very early they have run on before us, urged by the greatness of their love. We, incapable as yet of this sublime encounter, looking in their magic mirror, listening to their stammered tidings, may see far off the consummation of the race.

According to the measure of their strength and of their passion, these, the true lovers of the Absolute, have conformed here and now to the utmost tests of divine sonship, the final demands of life. They have not shrunk from the sufferings of the cross. They have faced the darkness of the tomb. Beauty and agony alike have called them: alike have awakened a heroic response. For them the winter is over: the time of the singing of birds is come. From the deeps of the dewy garden, Life—new, unquenchable, and ever lovely—comes to meet them with the dawn.

Et hoc intellegere, quis bominum dabit bomini?

Quis angelus angelo?

Quis angelus bomini?

El te petatur,

In te quaeratur,

Eld te pulsetur,

Sic, sic accipietur invenietur, sic aperietur.

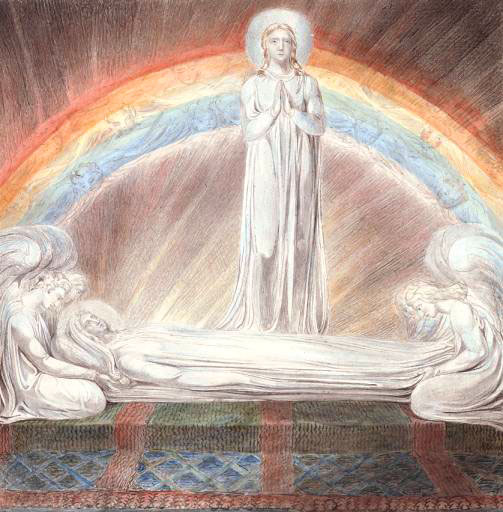

Death of the Virgin

William Blake

Next: APPENDIX: A HISTORICAL SKETCH OF EUROPEAN MYSTICISM

FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE CHRISTIAN ERA TO THE DEATH OF BLAKE